The Instrument of Government (1653) and The U.S. Constitution (1787): A Comparison

How truly unique was the U.S. Constitution at its ratification?

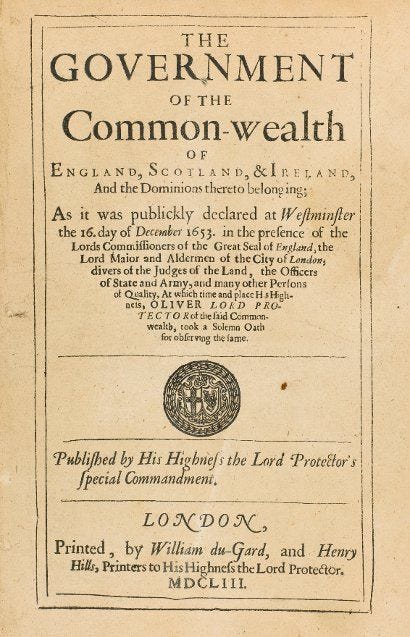

The following is Part I of a comparative series between the United States Constitution and another. This one is much less known, but there is evidence that it influenced the Founding Fathers in their framing of the United States Constitution. The document in question is the Instrument of Government, drawn up in 1653. It is to this day Britain’s only attempt at creating a constitutional government from scratch. A constitutional, republican government that is. Let me explain.

In 1642, the debate over where true sovereignty lay in Britain, whether the monarch alone or the monarch-in-Parliament, spilled over into the English Civil War or the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. (England, Scotland, and Ireland – poor Wales, I know it is unfair. And I can say that cause I have Welsh heritage, so no letters please.) In 1646, the king, Charles I, surrendered to Parliament. But, realizing there were splits within the parliamentary party, Charles utilized them to open up a renewal of the conflict in 1648, this time pitting his Scottish subjects against his English ones as well as helping spawn multiple royalist risings. Charles was good at scheming. Alas for his plans, Parliament’s New Model Army was a ruthless military machine. It crushed the internal revolts and destroyed the Scots army in the running battle of Preston. At the latter engagement, the army was led by one of its greatest general officers – a certain Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658). However, where once Parliament was willing to work out a settlement with King Charles, now the radical faction within it, as well as the leadership of the New Model Army, determined that the king was a “man of blood.” In January 1649, they put him on trial for treason (the trial was a legal and constitutional farce – how can the king be convicted of treason against himself?). The trial’s ending was a forgone conclusion, and Charles I knew it. The court sentenced him to death by beheading. On January 30, 1649, Charles went to the scaffold a martyr for his ideal of Christian kingship. When the axe fell, Britain entered a new era.

How new that era was is still too little appreciated. England, Scotland, and Ireland – kings had molded them all. Their entire political organization had evolved with kings at the head since the early Middle Ages. Parliament itself had been brought into being by kings in both England and Scotland in the thirteenth century. Every statute law in England was issued in the king’s name and backed by his authority. How could any of these states cope without having a king to rule them when everything – literally everything – had evolved, whether for good or ill, through the office of kingship?

Parliament was not unaware of this challenge and took immediate steps to rectify the issues at hand. In early February 1649, within ten days of Charles I’s execution (judicial murder more like it), Parliament abolished both the monarchy and the House of Lords in the English Parliament. For four years, the government under what was known as the Rump Parliament continued. In April 1653, though, Oliver Cromwell, now Lord General of the New Model Army, marched into Westminster and disbanded the Rump. But Cromwell, though he is the closest comparison to a dictatorial figure the British Isles has produced, was eager to impose a new constitutional settlement upon England and Britain more widely. For several months, an alternate Parliament was attempted – known as the Barebones Parliament after the name of one of its members, Praise God Barebones (Puritans are odd). While the new assembly was directed to work with the Army and was assembled from the broadest possible base, its sparse attendance meant religious, political, and legal reforms, all which were sorely needed, could not be discussed, let alone implemented. This situation vaulted in the opposite direction when towards the end of the year, the radicals in parliament attempted to impose new church reforms. Alarmed, the moderate majority countered in a bizarre fashion: on December 12, 1653, they showed up early in the Commons chamber, advanced themselves as a majority, and simply voted the Barebones Parliament out of existence. They then walked up King Street to Whitehall and delivered their mace of authority and Parliament rolls to a stunned Lord General Cromwell. England was without a government again.[1]

In my next piece, we will pick things up from here.

[1] M. Kishlansky, A Monarchy Transformed: Britain, 1603-1714 (London and New York, 1996), 205-6.