John Armstrong, Jr. – The Worst Secretary of War in American History

Part I in a series on Armstrong's failed tenure as Secretary of War.

In recent months, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth has found himself embroiled in a political controversy due to his problematic use of the Signal messaging app. This has led to questions about his competency, his character, and whether or not he ought to resign.

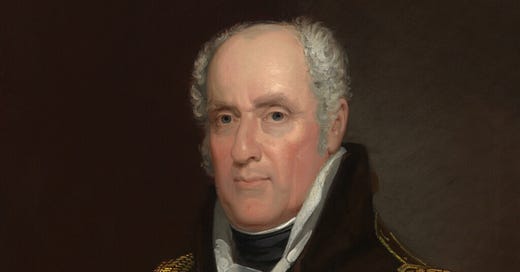

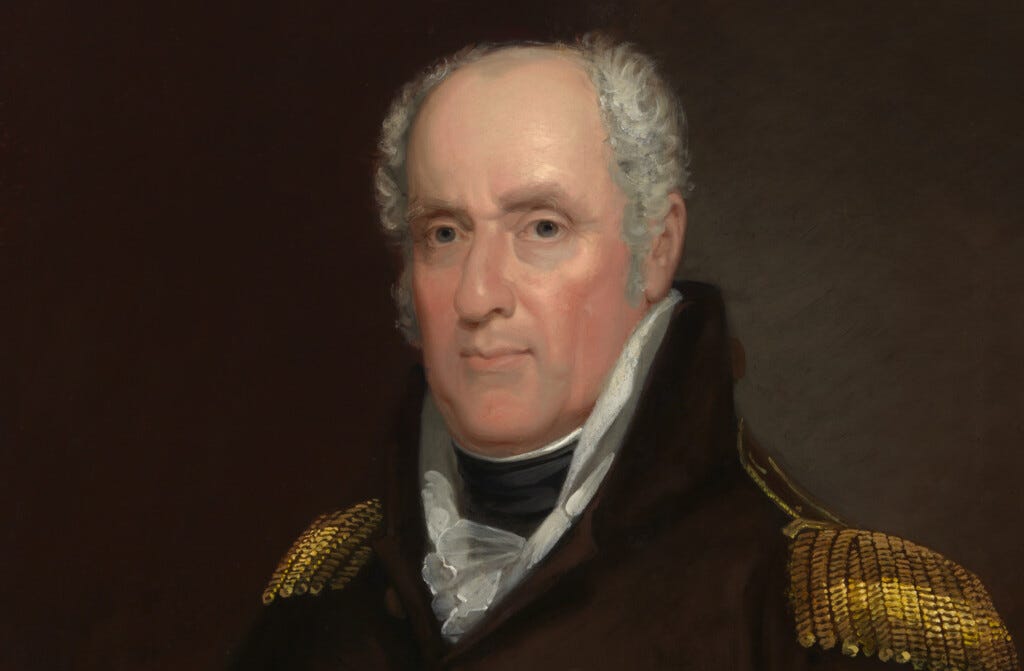

Potentially putting military intelligence at risk on at least two occasions is a serious blunder for any Secretary of Defense to make. However, Hegseth is still a long way away from being the worst Secretary of Defense or Secretary of War[1] in the history of the United States. That dishonor still goes to John Armstrong, Jr. (1758–1843).

Before elaborating on Armstrong’s failures, it is important to note that the early history of the cabinet secretaries is littered with incompetence. The foremost historian of the cabinet system today, Dr. Lindsay M. Chervinsky, has explained why in her latest book, Making the Presidency: John Adams and the Precedents That Forged the Republic. The reasons were threefold: the positions were not as prestigious as they would become, the pay was terrible and the hours long, and the jobs were year-round affairs which kept their occupants in the capital city while members of Congress and even the President could leave for their homes in the countryside.[2]

Journalist and historian Richard Brookhiser has said that the first cabinet under George Washington was the best the United States ever had. Thomas Jefferson at State, Alexander Hamilton at Treasury, Henry Knox at War, and Edmund Randolph as Attorney General – every subsequent cabinet looks like a “pick-up team” in comparison.[3]

For the Secretaries of War, the incompetence set in early. Timothy Pickering was the second Secretary of War after Knox. He proved to be a placeholder, though he is unlikely to have flourished in the role if his career as Secretary of State under Washington and Adams is anything to go by. The next Secretary of War, James McHenry, seems to have been a well-liked man from the moment he became one of Washington’s aides-de-camp during the Revolution. Yet, Washington and Hamilton both believed he was out of his depth as an administrator and especially as head of the War Department.[4] However, the lackluster performances of gentlemen such as Pickering and McHenry would pale in comparison to the dismal management provided by John Armstrong, Jr. during the War of 1812.

Armstrong did have military and political experience behind him before President James Madison nominated him as Secretary of War in 1813. In the late summer of 1776, the young Armstrong joined the Pennsylvania regiment of James Potter. Soon enough, he was noticed by Brigadier General Hugh Mercer, a close friend of General George Washington. Mercer made Armstrong a brigade major and one of his aides-de-camp. This would not last long, however, as Mercer was killed at the Battle of Princeton in early 1777.

Not long afterwards, Armstrong was discovered anew by Major General Horatio Gates, who added him to his staff. In this capacity, Armstrong participated in the Battle of Saratoga and became a great favourite of Gates.[5] Their alliance eventually culminated in the infamous Newburgh Conspiracy of 1783, where Armstrong may have served as the author of the Newburgh Address, which compiled the grievances of the officers of the Continental Army. This movement might have led to a potential military coup if Washington had not masterfully handled the situation.[6]

After the War of Independence, Armstrong moved into a civilian career, first as a delegate to Congress under the Articles of Confederation in 1787 and again in 1788. In 1800, having moved from Pennsylvania to New York, he was elected as a senator for the latter state, serving as a member of the Democratic-Republican party under the leadership of Thomas Jefferson.[7]

Jefferson was subsequently elected as the third President of the United States at the beginning of 1801. Interestingly, when constructing his cabinet, Jefferson solicited General Gates’s advice as to who should be his Secretary of War. Gates put forward Armstrong as a candidate. Jefferson eventually selected Henry Dearborn instead. Armstrong does not seem to have wanted the role for himself, having heard that he would be little more than a glorified clerk.[8] His selection as Secretary of War, however, was only to be deferred.

[1] Before 1947, and the broad-ranging Department of Defense, there were two secretaries for military and naval matters: the Secretary of War and the Secretary of the Navy.

[2] L. M. Chervinsky, Making the Presidency: John Adams and the Precedents That Forged the Republic (Oxford and New York, 2024), 15.

[3] For the creation and early history of the Cabinet, see L. M. Chervinsky, The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution (Cambridge, MA, 2020).

[4] Chervinsky, Making the Presidency, 47-8; E. G. Lengel, General George Washington: A Military Life (New York, 2005), xxx-xxxi, 362.

[5] For Gates’s career and influence on men such as Armstrong, see George A. Billias, “Horatio Gates: Professional Soldier,” in George Washington’s Generals and Opponents: Their Exploits and Leadership, ed. George Athan Billias (New York, De Capo edition, 1994), 79–108.

[6] John Armstrong Jr. | George Washington's Mount Vernon

[7] John Armstrong Jr. | George Washington's Mount Vernon

[8] C. E. Skeen, John Armstrong, Jr., 1758-1843: A Biography (Syracuse, 1981), 46.