John Armstrong Jr., Part II: The Fall of Washington

With the enemy at the gates, America needed leadership. Armstrong disappeared.

In 1812, the United States declared war on Britain, a conflict that would become known as the War of 1812. It was to be the most ill-managed and ill-fought war in American history. By late 1812, the United States had been rebuffed on both land and sea multiple times. In December, Secretary of War William Eustis resigned under pressure from a Congress in search of a scapegoat.

President James Madison began casting around for replacements, and Armstrong’s name immediately came up in conversation. However, Madison knew Armstrong from their days in Congress together, and he did not like him. There was not much love lost on Armstrong’s side either. However, as his biographer said, the position “fell to him almost by default.”[1] Madison needed an experienced military man for the post, and given the circumstances of the war, no one else seemed to want the job.

In January 1813, Madison formally offered the role to Armstrong, and the latter accepted. However, he was confirmed by the Senate by the small margin of 18 to 15. While some might have had confidence in Armstrong’s abilities, others expressed doubts. “Few Cabinet officers in American history have ever undertaken so important a task with so little support.”[2]

Armstrong took over the War Department in February 1813. The Department itself was already in a mess due to the frustrations of the war and the inaction of Congress. The quality of the general officers Armstrong had to work with was not much better. The War of 1812 was partially a bungled mess for the American military because there were only two types of generals to choose from: old and outdated or new and untried.

Madison and Eustis had placed their trust in the old guard, and the results were disastrous. Generals William Hull and Henry Dearborn—a former Secretary of War himself—proved at times embarrassing and at others merely ineffective. Although a new generation of officers was beginning to emerge—most notably Winfield Scott, who was earning distinction in the campaigns of 1813 and 1814—the overall quality of American military leadership lagged far behind that of their British counterparts. The gap in talent was both glaring and costly.

The activities of American commanders on the frontiers were more promising. William Henry Harrison was waging a war against Britain’s Shawnee allies in the Midwest with some success, and Andrew Jackson would achieve comparable results against the Creek confederacy in the south. Most impressively, the US Navy was giving as good as it got against the Royal Navy and won three straight ship actions against the British in 1812.[3] However, the Navy could have been performing even better had not the Republican governments under Jefferson and Madison denuded it of funds in the run up to the war. Given all this, Armstrong could be forgiven for failing to adequately manage the American war effort. It was perhaps beyond the capacity of anyone except a military genius, which he definitely was not. Nevertheless, his abysmal performance during 1814 is what turned him from a lackluster Secretary of War into the worst one in American history.[4]

By 1814, the American government knew it needed to end the war as soon as possible. President Madison had, in fact, been sending repeated requests for peace commissions since the latter months of 1812. Britain too wanted this war over quickly: they were already fully engaged in fighting Napoleon in Europe.

However, in early 1814, Napoleon was defeated (barring his brief Hundred Days Return in 1815). The British could now transfer portions of their army to the American theater. A small force of around 4,500 men was dispatched under Major General Robert Ross to the Chesapeake Bay. The British had no desire to reconquer their former American colonies. What they wanted was to demonstrate their strength vis-à-vis American weakness. They would mount a strike force and directly attack the American capital of Washington, D.C. Such a strike would convince the Madison administration to sue for peace on any terms and leave the British with the whip hand in negotiations. It was Armstrong’s job to blunt this attack in the late summer, early autumn of 1814.

He failed. Indeed, the coming British onslaught was made much worse by infighting within Madison’s cabinet. Armstrong and the Secretary of State, James Monroe, absolutely hated each other’s guts and had for a number of years. Their constant rows were weakening the administration's resolve when it was needed most. Armstrong also repeatedly proclaimed to anyone that would listen that the British were not going to strike Washington. They might strike Baltimore, given its strategic significance to the American war effort, but not the capital. This led to his complacency: he made almost no preparations to defend the city, aside from placing Moses Porter in command.

Madison, desperate for an officer who would do something, created the tenth military district and put William Winder in command of it. Armstrong and Winder clashed repeatedly, and the Secretary of War resented these constant interferences by the President.[5] Instead of formulating a strategy that would defend the capital by putting personal differences aside and submitting himself to the call of duty, Armstrong failed his President and his country in an hour of need.

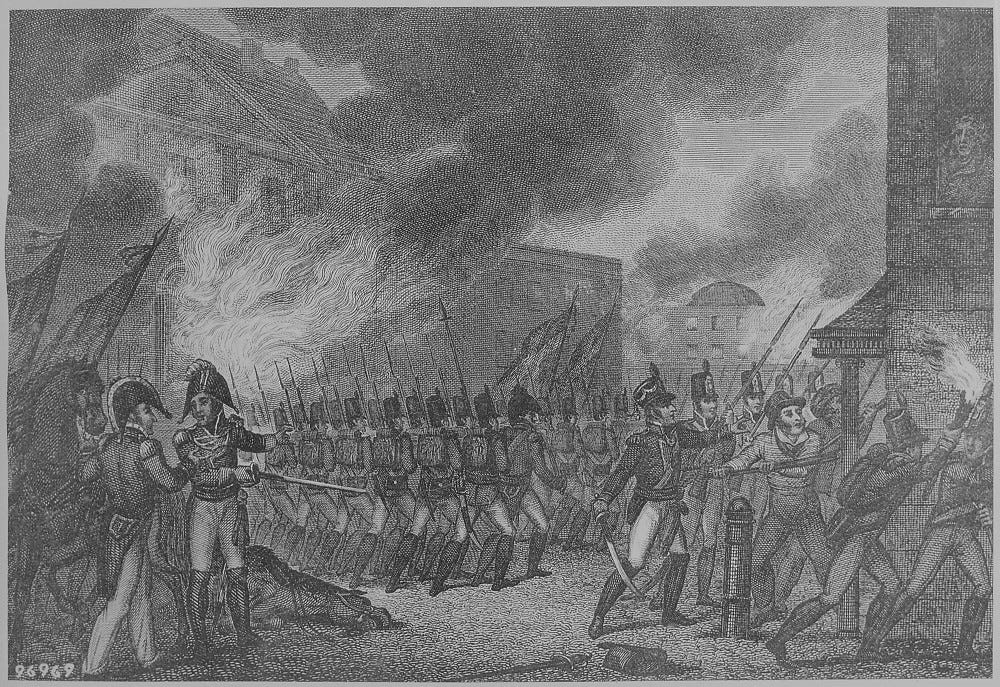

The results of Armstrong’s inaction and complacency were startling. The British army under General Ross clashed with General Winder’s meagre forces at Bladensburg, Maryland, ten miles north of the White House, on August 24, 1814. The British came on strong, and the militia components ran from the field so quickly that the battle became known as the Bladensburg Races.

Armstrong likely expected this reaction from the militia. At a council of war with Winder and Madison’s entire cabinet, he stated he did not believe the militia would be capable of withstanding the veterans of the Peninsula War. Yet he presented no other plan himself.

Indeed, one reason Bladensburg proved such a debacle was that it was “generalship by committee.” General Winder was technically in command, but with Madison’s full cabinet present, everyone was trying to assert himself. Secretary Monroe attempted to reform the American lines before the battle commenced and then tried to rally the militia as they fled. President Madison himself rode onto the battlefield, pistols holstered at his side, before being warned that he was dangerously close to the enemy.

The scene was one of utter chaos.[6] General Winder retreated toward Baltimore, effectively abandoning the capital. President Madison, joined by Monroe and the rest of the cabinet, rushed back to Washington in a desperate attempt to coordinate an evacuation. Armstrong, by contrast, slipped away quietly, making no effort to assist in the defense or rescue efforts. That night, British forces entered Washington, D.C., plundered the White House, and set it ablaze—along with nearly every other public building in the city—before withdrawing to their ships. According to legend, as they retreated, they were met by a massive storm that lashed the city, as if nature itself recoiled at the destruction.

Armstrong returned to Washington, D.C., on August 29. There, he was met with hostility, with people openly blaming him for the disaster. He was told as much by President Madison himself.

Armstrong did not believe the accusations against him were justified, but he understood he was fighting a losing battle. He offered his resignation to the President and also expressed his willingness to step aside and let Madison consider his options. While Madison declined to formally accept the resignation, he permitted Armstrong to withdraw to Baltimore, effectively ending his role in the administration.

While there, Armstrong wrote to the editors of a local newspaper defending his actions. His defense impressed a number of writers from then to the present, with some even suggesting he should not be blamed for the disaster. However, ultimately, the buck stopped with him. Unimpressed by the people he had to work with and knowing that the President was merely biding his time before firing him, Armstrong submitted his official resignation on September 4, 1814. James Monroe became joint Secretary of State and Secretary of War on September 25.[7]

Is there anything to be said in defense of John Armstrong Jr.’s tenure as Secretary of War? Some of the points he raised in his letter to the newspaper carry a measure of truth. He was placed in an almost untenable position—tasked with defending the nation while serving under a president and alongside colleagues who disliked him. He was forced to rely on inexperienced generals, poorly trained soldiers, and inadequate supplies. In that regard, Armstrong deserves a measure of sympathy. The war was not of his making, and it was already going poorly by the time he assumed office.

Still, the debacle at Bladensburg stands as the defining stain on Armstrong’s legacy. At a moment when the United States desperately needed decisive leadership, nearly everyone around him made some attempt to rise to the occasion—except Armstrong. His failure was not just strategic but moral: a passive, almost indifferent resignation in the face of crisis. For all the mitigating factors, it is this failure that ultimately defines his tenure. In the end, John Armstrong Jr. must be remembered as the worst Secretary of War in American history, bearing a significant share of the blame for turning the War of 1812 into one of the most humiliating chapters in the nation’s military record.

[1] Skeen, John Armstrong, 123.

[2] Skeen, John Armstrong, 125.

[3] A. Lambert, The Challenge: Britain against America in the Naval War of 1812 (London and New York, 2012).

[4] Armstrong’s string of bad decisions in 1813 is covered in Skeel’s biography of him as well as G. Wills, James Madison (The American Presidents Series) (New York, 2002), 117-28. Due to the short nature of this piece, they are not addressed here.

[5] Wills, James Madison, 135-6.

[6] These events and many other details are available at Embattled President James Madison Under Fire at Battle of Bladensburg.

[7] Skeel, John Armstrong, 199-205.